Always, Sometimes, Never

By Bethany Neel and Dee Crescitelli

![]() Always, Sometimes, Never

is a classroom routine that can be used in any grade level and for any domain of mathematics.

Students are presented with a statement and are asked to determine whether it is always, sometimes, or never true.

The beauty of this routine is revealed as students explore examples, counter-examples, make generalizations, and

provide evidence to justify their conclusions.

Always, Sometimes, Never

is a classroom routine that can be used in any grade level and for any domain of mathematics.

Students are presented with a statement and are asked to determine whether it is always, sometimes, or never true.

The beauty of this routine is revealed as students explore examples, counter-examples, make generalizations, and

provide evidence to justify their conclusions.

Let's look at an example.

You decide: Is that statement, always, sometimes, or never true? How would you justify your thinking?

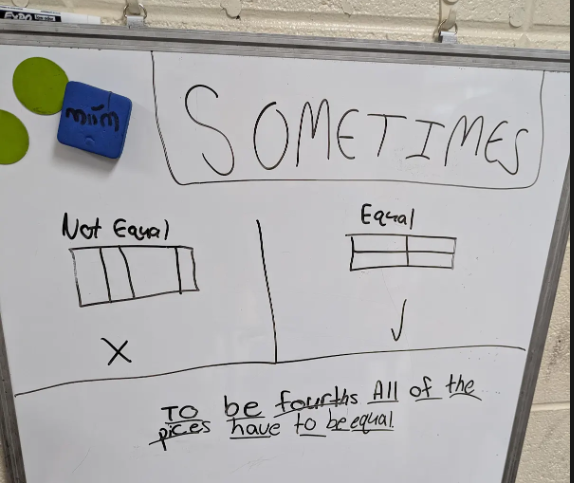

This particular prompt can be used with first graders working with fourths, continuing through intermediate grades. Here is some student work generated by third graders:

What did you learn about these students' thinking from this image? What questions might you ask them? Did they convince you that this statement is sometimes true?

Using this routine pushes students to think about when generalizations do and do not apply. It requires nuanced thinking and the consideration of a variety of cases. Proving a statement is sometimes true can be relatively straightforward, as you can provide one example and one counter-example. However, proving a statement is always true or never true can be more challenging for students. They will sometimes test a case or two, and assume that proves the statement is always or never true, not considering how they might prove (or disprove) their thinking without testing every possible case.

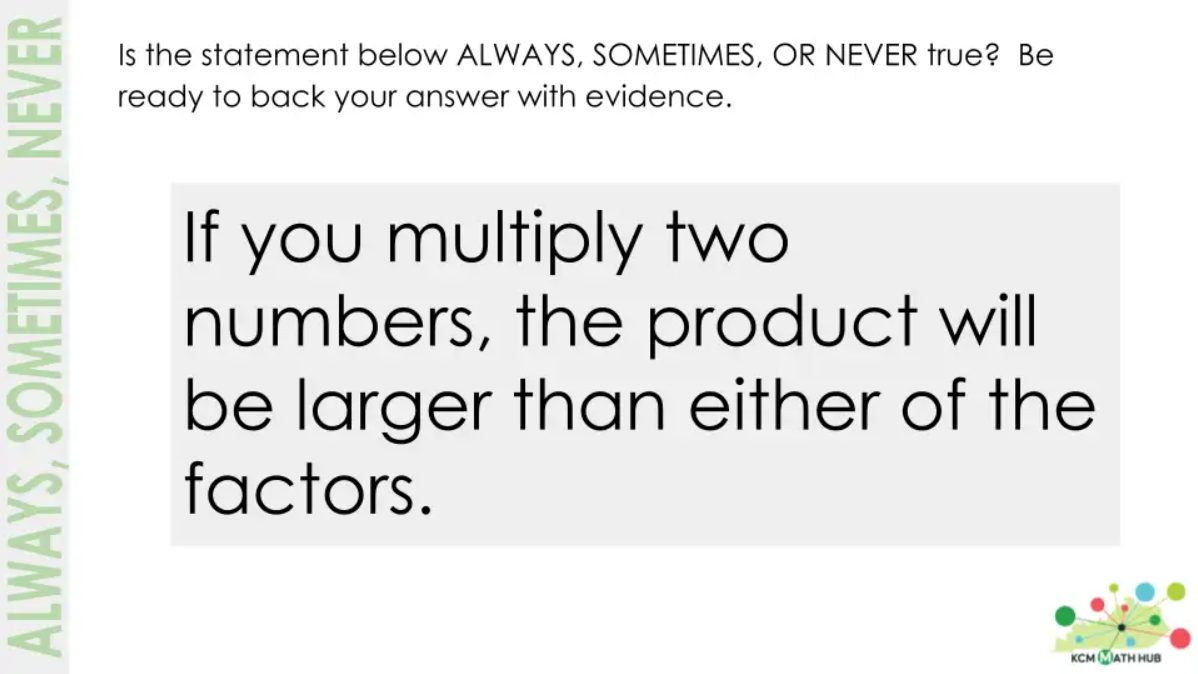

Let's look at another example that might be used in a classroom starting in third grade.

How would you (or your students) begin to think about this statement? As students first learn about multiplication, they might draw the conclusion that multiplication makes numbers larger. Presenting a statement like this leads students to consider cases such as multiplying by 0, 1, fractions, decimals, or negative numbers.

Engaging in the Routine:

Always, Sometimes, Never can be implemented in a variety of ways. Depending on the statement and goal, the routine could be as short as two to three minutes or take much longer. The routine begins with presenting the students with a statement to consider.

You might ask students to:

- Consider the statement individually, and then turn and talk with a partner.

- Think individually and then move around the room to areas labeled Always, Sometimes, and Never- then work with others to prepare evidence to convince other students.

- Gather in groups and create written evidence and cases to justify their thinking.

- Work independently or in groups as a formative or summative assessment task.

When I use this routine in my classroom, I usually have students move into groups to show their initial thinking, and then talk with the people who agree with them. (These posters can be hung in the room to show students where to go.) Often, as they generate ideas, they will convince themselves of a different answer. Students are encouraged to revise their thinking and physically move to another location as needed. Finally, students use their examples, logic, and cases to try to convince the other groups to agree with them, and we debrief as a class.

Advice for Choosing Prompts:

There are some great resources (see below) with prompts, but you can also create your own prompts tailored to the specific content and grade level you teach.

Some types of prompts you might consider:

- Non-math prompts - Start with prompts that draw from students' everyday experiences to help them understand the routine and what kind of evidence can support their ideas (e.g., First graders are 6 years old. Sometimes.)

- Vocabulary-focused prompts - Begin with statements that can be evaluated by using the definition of a certain word in the statement; these prompts usually lead to shorter discussions (e.g., The top numeral in a fraction is called the denominator. Never; A rectangle is a square. Sometimes)

- Exceptions and Expirations - These tasks ask students to consider new or special cases. The prompts focus on statements that may be true in situations and cases that are most familiar to students, but do not always remain true. They encourage students to consider various possible cases and types of numbers. (e.g., A whole is more than a half. Sometimes; If you multiply two numbers, the product will be larger than either of the factors. Sometimes)

- Exploration prompts - These require more thinking and exploration time, and may lead to new learning as students consider a variety of cases. (e.g., If you add two odd numbers, the sum will be even. Always)

- Student-created conjectures or statements - As students are learning, they may notice a pattern or relationship and wonder if it holds true always. This is a great time to jump into an Always, Sometimes, or Never. You could also ask students to create (and provide the answer and evidence for) their own prompts. Students may also have the opportunity to facilitate the routine with the class.

Resources for Implementing the Routine:

- KCM slide deck with sample prompts

- Math = Love: Measures of Central Tendency with links to statements for other middle school topics

- Nrich tasks and support for statements related to operations

- Nrich geometry tasks and support

Final Thoughts:

Be sure that the prompt you choose fits the goal you have for the routine that day. Is it a statement that students can evaluate in a few minutes, or do you need significant time for students to explore? Start small, with statements related to students' everyday experiences so that they can learn to provide evidence and prove their thinking. Be sure your prompt is carefully worded and that you have thoroughly considered all cases to prepare. Then, jump right in and let your students show you their amazing thinking! This routine is a favorite in my classroom, and one my students ask for again and again. I try to predict what they might say and what evidence they might give, so that I can be an effective facilitator, but most of the time, they surprise me!

![]() Collection: Routines COMING SOON

Collection: Routines COMING SOON